Networks, Power and Change: The cult communities and the religious coordinate system of the Roman world

Mystery cults’ access and attraction: elites and outsiders

The mystery cults were of little interest to the absolute upper class of society, which had extensive influence and access to the official urban cults. Their members focused on the public religious functions associated with their offices as magistrates and priests. Here the prestige was in the visibility and the officialRecognition within the framework of the city community. The situation was completely different for those who were more marginal figures in the hierarchy of traditional cults. Freedmen, people from the lower ranks of the military, as well as small administrative staff found a field in the mystery communities where they could achieve important positions through commitment and determination.The promise of integration and social advancement was a crucial incentive for many of these outsiders to join the cults.

Military Structures and Networks: The Distribution of the Cults

The organization of the cults, especially their distinct hierarchy, carried unmistakable military features. The community of mystices was closely linked to the emperor to whom the highest loyalty was due, and addressed their prayers to the god Mithras. The role of the military as a widely branched network was crucial for the rapid and wide spread of the cult. The soldiers whodistant provinces were transferred, carried their religious beliefs and rituals, creating a lively exchange of information between the individual communities. These military-organized structures not only offered a strong internal community, but also radiated into public space. who is within the closely connected cult community until”Pater” had been brought, could be sure that he would also be perceived as an important personality outside of the Mithraum. The networks made by the cult were not limited to the interior of the community, but also worked in the city and possibly even beyond regional borders.

Patronage, dependencies and social reflections

It cannot be ruled out that the interdependencies that prevailed in everyday urban life also reproduced in the circle of mystices. At the same time, relationships and patronage that developed within the cult community could find their correspondence in society. The cults were not only religious associations, but also hubs of socialNetworks that reflected both power structures and dependencies. This double anchoring in cult and society made the mystery communities dynamic actors who offered far more than just religious experiences.

Syncretism and Competition: Mithras and Jupiter Dolichenus

Mithras was in fact not the only god of oriental origins who enjoyed particular popularity in the Roman military. Another example is Jupiter Dolichenus, whose origins are precisely located in the village of Doliche on the upper Euphrates. Like Mithras, it was also a syncretistic new creation that developed in Italy, the Rhine andDanube provinces spread. His depiction in the Roman military robe with ax and lightning bundles as attributes symbolized the combination of oriental spirituality with Roman power. But the cult of Jupiter Dolichenus disappeared after the destruction of his temple by the Persians in the middle of the third century. This was not an isolated case, but an expression of a comprehensive change in thereligious Coordinate system in the Empire, which at that time irrevocably changed.

Imperial Religion and the Pantheon’s Change

Many Roman emperors combined their personal destiny with certain deities and privileged them over others. The unfortunate Elagabal tried in vain to put the god from his Syrian hometown of Emesa at the head of the Roman pantheon and thus failed miserably. Just a few decades later, Aurelian raised the sun god Sol Invictus to his patron god,And Constantine the Great also initially showed sympathy for Sol before embarking on the path to Christianity. During this time, expectations of the gods changed dramatically: the perspective of redemption that the mystery cults offered their followers became a general expectation of divine beings. The cults were increasingly detached from their local origins and developedto a nationwide phenomenon. The emperors carefully respected which gods were worshiped and increasingly intervened more frequently in religious life. Thus, the Christians were first persecuted, then tolerated and finally raised to a privileged religion.

The end of the ancient cults and the rise of Christianity

This development followed a certain logic: No cult embodied the universal claim to power of the Roman Empire better than Christianity, which understood itself as universal. While the supporters of the old cults had to dive into the hidden more and more, Christianity was raised to a state religion. In a direct comparison, the traditional mystery cults had againstChristianity no chance. Her weakness was not only in the fragmentation and exclusivity of membership, but also in the lack of central organization. The Church, on the other hand, offered a unified structure, central teachings and a message of salvation aimed at all people – not just a small group of initiates.

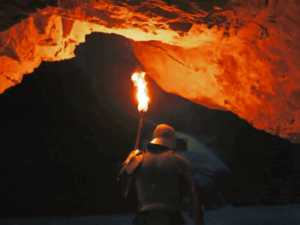

San Clemente in Rome: Symbol of religious change and repression

The imbalance of these balances of power is particularly evident in the Church of San Clemente in Rome. Here three places of worship are arranged one above the other, like layers of the story that lie on top of each other. The present 12th century church has been rebuilt several times, including the ruin of a late antique basilica, built under Pope Siricius in the 4th century and destroyedin the 12th century. Even below, concealed under the former courtyard of a large building, which was once a coin, is a mithraum from around 200 AD, this sanctuary, with its star-decorated ceiling, the barrel-vaulted room and the characteristic altar with Tauroctony, resembles other mithraes in the Roman Empire. Between 250 and 275 AD was over theMithraum built a large hall that could have served as a Christian church. By 392 at the latest, this was converted into a three-aisled basilica – a symbolic act that manifested the triumph of Christianity over the old cult. The Christian Church had literally laid down on the sanctuary of Mithras and forced the old cult into oblivion.

The end of the cults of the mystery: edicts, prohibitions and the downfall of a religious epoch

A similar fate soon befell the God Mithras himself. In 392, Emperor Theodosius issued the ban on the Eleusinian cult, which finally initiated the end of the centuries-old mysteries. The last initiates, as the Neoplatonic philosopher Eunapios of Sardes reports, had to work in secret and keep their identity secret. with the ban, the destruction ofShrines and the rise of Christianity erupted a flood of catastrophes that were perceived by contemporaries as the downfall of entire cultural landscapes. The religious world of the Empire was fundamentally remodeled, and with it not only the ancient gods, but also the social networks, career opportunities and communities that had formed around them.

Cult communities as mirror and motor of social dynamics

The history of the mystery cults in the Roman Empire impressively shows how closely religion, society and political power were intertwined. The cult communities not only offered spiritual home, but were also social networks, career jumpers and mediators of patronage and dependency. Their rise and fall reflects the profound changes thatImperium lived through – from belief in the gods to syncretistic forms of cult to the triumph of Christianity. The old mystery cults ultimately remained in the shadow of the new religion, whose universalistic aspirations and organizational strengths they suppressed and largely eradicated their place in the collective memory of mankind.