Pisonian Conspiracy – Intrigues, Betrayal and End of a Reign

In the spring of the year, when the Pisonian conspiracy took its course, Rome was an atmosphere of insecurity and distrust. The city was characterized by political tensions, social upheavals and growing dissatisfaction with the rule of Emperor Nero. The Senate Saristocracy, which traditionally is the bearer of the Roman values and as a counterweight to theImperial power understood, increasingly saw himself marginalized. In the midst of this changeable mood, a group of conspirators formed around the Senator Gaius Calpurnius Piso, who came from a traditional family whose roots date back to the early republic. Piso was not only through his origins, but also through his personal charisma, hisgenerosity and his rhetorical skills predestined to become the leader of such a movement. Nevertheless, his character was controversial, because he was said to be too fond of the joys of life and waste, which made the contemporaries’ judgment of him ambivalent.

The creation and composition of the conspirator group

The group of conspirators consisted of a large number of different people who came from different social classes. In addition to senators and knights, there were also soldiers and even women who were willing to risk their lives for their common goal. The motives of those involved were extremely different: while some, like the poet Lukan,Personal hostility to Nero, for having suppressed her works, drove others, such as Senator Quintianus, to public humiliation by the Emperor to participate in the conspiracy. The Praetorian prefect Faenius Rufus, in turn, saw the movement as an opportunity to free himself from the shadow of his colleague Tigellinus. But there were also idealists like the designated onesConsul Lateranus, who worried about the welfare of the state, and political adventurers who hoped for their own careers by falling through Nero’s overthrow. The meetings of the conspirators were characterized by heated discussions and changing plans, with the participants repeatedly reinforcing each other in their rejection of the emperor, but without becoming a uniform strategyfind

The planning of the assassination and the first setbacks

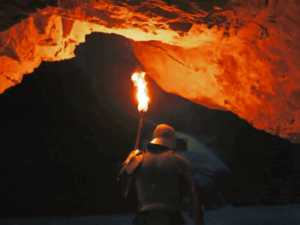

The uncertainty within the group grew when it became known that a woman named Epicharis had tried to win the Sea Officer, Volusius Proculus, based in Misenum, for the conspiracy. Proculus, however, immediately revealed the conversation to the authorities, even if he could not name any names. This development triggered a wave of panic among the conspirators, fearing thatthat their plans could be revealed. As a result, the pressure to act quickly became greater. At first, it was considered to murder Nero in Piso’s villa near Baiae, but Piso himself rejected this plan, fearing retaliation by the emperor’s supporters. Finally, it was agreed that the upcoming Ceresfest with its circus games was an opportunity for the assassinationto use. The plan envisaged that Lateranus should approach the Emperor and distract him by fake pleading, while the co-conspired Praetorian officers would overpower the defenseless emperor. Flavius Scaevinus, a senator known for his debauchery, had agreed to lead the first blow and prepared a dagger for the act.

Betrayal from your own ranks and the failure of the plan

The day before the planned attack, there was a serious turn. Scaevinus had a long conversation with the knight Antonius Natalis, another important member of the conspiracy group. He then commissioned his released man to Milichus to sharpen the dagger and to provide dressing material and medication. He gave his favorite slave freedom andwrote his will, which aroused distrust among the house members. After consulting his wife, Milichus, who recognized the connections and hoped for a reward, decided to report what he saw to the authorities. After initial rejection, he managed to step before the emperor and describe his observations. The dagger was presented as evidence, and Scaevinuswas confronted. Despite his calm and calm reaction, he could not dispel the doubts. The separate interrogations of Scaevinus and Natalis led to contradictory statements, after which both were arrested and tortured. Under the pressure of torture, they collapsed and made comprehensive confessions in which they burdened numerous conspirators.

The wave of arrests and the tragic end of those involved

The confessions triggered a chain reaction: More and more conspirators were arrested, and many of them betrayed even their closest friends or family members for fear of their own lives. The fate of Epiccharis, who remained steadfast despite severe torture and eventually took his own life, so as not to betray anyone, was particularly tragic. Tacitus raises her behavior asshining example, while at the same time criticizing the weakness of many freeborns and members of the upper class who denounced their neighbors without torture. The conspiracy collapsed when most of the accomplices were exposed and arrested. Many of them were executed, including Lateranus, who did not even get the opportunity to get away from his familysay goodbye. He was killed by the Tribune Statius, who himself belonged to the conspirators.

The role of Seneca and the consequences for Roman society

The philosopher Seneca also fell suspicious, although his direct involvement could not be proven. He confirmed to the Tribun Silvanus that he had rejected Piso because he felt uncomfortable. When Nero found out about this, Seneca had Seneca brought the order to suicide by Silvanus. Seneca said goodbye to his friends, opened his wrists and tookPoison, but death did not occur. Eventually he went to the steam bath to die from the heat. His wife Paulina also chose to die and cut open his wrists, but was saved on Nero’s order. Tacitus emphasizes that Paulina’s voluntary death had even more splendor than that of her husband, who endured his death with stoic firmness.

The aftermath of the conspiracy and the end of Nero

The pisonic conspiracy ultimately failed due to the lack of determination of its actors and because they could not formulate any common political goals beyond Nero’s elimination. A few months after the failure of the conspiracy, Annius Vinicianus tried to overthrow the emperor, but this attempt was also unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the conspiracy had the regimeNeros destabilized in the long term and shaken confidence in his rule. The events showed how deep the trenches had become within the Roman elite and how much the political system of the late imperial period was characterized by intrigues, betrayals and personal insecurities. Ultimately, the persistent instability led to Nero being overthrown himself a few months later andended his life on the run. The Pisonian Conspiracy remains an impressive example of the dangers that can arise from the interplay of personal ambition, political dissatisfaction and social turmoil, and marks a turning point in the history of the Roman Empire.